TWENTY-SECOND TO NONE

The History of the 22nd (N.Z.) Battalion

By Terence Power Mclean

FORWARD

“My name is Andrew – A-N-D-R-E-W. There is no ‘s’ on it and I’m the boss.”

He looked it. He was the first commander of the newly-formed 22nd New Zealand Infantry Battalion and this was his first parade.

As a lance-corporal at the age of 20 in the First World War he had won the Victoria Cross for charging and destroying German

machine-gun posts. He had kept to soldiering between the wars. Now, at the instance of another old corporal, the Nazi Hitler,

a new war had come, and to Leslie Wilton Andrew there had been given the responsible task of forming one of the battalions,

one of the many, many battalions, which would be needed to fight the German horde.

If Leslie Wilton Andrew had any doubts of his capacity for the task he did not show them on this first parade. His figure was stiff,

his black moustache bristled and his voice had a rasping edge. “I’m the boss,” he said.

Yet for all the pride in the statement of ownership, Andrew, as it became clear later, was much more concerned with another thing

than with the fact that he had been given a command. The words penetrated to the furthest man on that parade ground. “Take a pride

in your unit. Remember, you are the Twenty-Second Battalion.”

It became clear later that Andrew not only loved the notion of a battalion but that he could come to love his battalion. For its

sake he was prepared to subject himself and every man in it to hard discipline to make the unit as good as he thought it ought to be.

He became “Old February” because he favoured the maximum, 28 days, in his punishments. He became loved and hated and feared and

respected and gradually the battalion took the shape he desired.

By experience, Andrew knew the perils of active service. By some mysterious affinity with Joseph Conrad, he knew that those perils

could more cheerfully be endured and more successfully overcome if, within his unit, there existed a feeling of loyalty. Of Conrad

Desmond McCarthy, the literary critic had said, “His thesis was not, as many supposed, adventure. It was the spirit of loyalty.”

To Andrew, a battalion was not enough. To be the boss of a battalion was not enough. To be enough, there must be a pride. Pride

could be a weapon, as invisible support for a wavering aim, a staff when duty fought with weariness and fear.

He used to say, “We are the Twenty-Second to None.” The phrase was repeated, mockingly, good-naturedly, sometimes bitterly, and in

the repetition men came to believe that it meant something to the battalion.

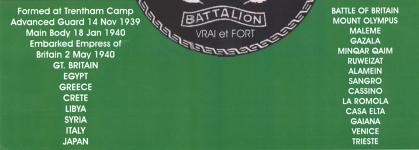

The 700 of the first parade multiplied. Andrew served his time and returned to New Zealand. The 22nd served in England, Greece,

Crete, the Western Desert, Italy and Japan. It suffered dreary days of defeat and pleasant days of victory. It played a small

but constant part in the grand drama. From all these circumstances, each one related because it concerned the unit, a pride and a

character was developed. Both were similar to the pride and character of the other New Zealand units and yet, because they concerned

the 22nd Battalion, they somehow became individual and distinctive to the unit.

This is an attempt to tell the story of the pride and the character which the unit developed to show that, from the beginning to end,

the stentorious message of the first parade was the abiding factor of the battalion’s history. More than 4,000 men in time thought it

good to “take a pride in their unit.” The feeling was of service both to them and to the unit.

CHAPTER ONE

12 Jan 40 – 13 Mar 40

Formation and Training

On 18 January 1940, the first parade of the 22nd New Zealand Infantry Battalion was held at the Trentham Military Camp, near

Wellington. The battalion had been formed on 12 January of volunteers drawn from the several provinces of the Central Military District, one of

the three military districts into which New Zealand was divided. To encourage company spirit, the four rifle companies were established on district

bases. Men from Wellington city and the immediate area were posted to A or Wellington Company; from Wanganui, Palmerston North, the Manawatu and

Rangatikei, to B or Wellington-West Coast Company; from Hawkes Bay and the East Coast district from East Cape to Cape Palliser to C, or Hawke’s

Bay Company; and from Taranaki to D or Taranaki Company. The headquarters company, which included battalion headquarters, was made up without

distinction of district of men with some precious territorial experience.

For some time prior to the formation of the battalion as a unit of the

Fifth Brigade of the Second New Zealand Division, officers had received training in an officer cadet training unit and NCOs in the Central District

School of Instruction. Lt-Col Andrew, the commanding officer and the adjutant, Lieutenant P.G. Monk, were regulars of the NZ Staff Corps. All of the

other officers were either plain civilians recently commissioned or territorial officers with service in the voluntary territorial units which had

functioned in the country from 1930 to 1939. Some of the senior NCOs were of the Permanent Staff, the non-commissioned establishments of the regular

forces.

Most of the other ranks were civilians. Some of the older men had served in territorial regiments before the abandonment

of compulsory universal training in 1930. Some had served as volunteers in the territorials. By far the greater number were without service background

of any kind. They had volunteered after the outbreak of war and were untrained and ignorant of military discipline.

In the first few days from the 12th, forms were filled in without great enthusiasm, civilian clothes were returned to homes, and suits of khaki denims of most

unattractive design and cut were issued. It was said in the ranks that the authorities had issued the denim because of their ambition to create a

“Sing Sing” atmosphere in the camp. The congregation of men on parade or in the mess hall, especially when some had their hair cropped, undoubtedly

created an appearance of woe.

On 15 January, a training programme was begun. By then, companies, platoons and sections had been

formed, a rough kinship was developing and the extraordinarily bad language of recruits in their first few days in camp was prevalent. A good deal of

language was directed at fatigues required for camp maintenance and some of it upon the commanding officer for his eagle eye on inspection. He was not

easily persuaded of difficulties in the performance of any task, not even in the cleaning of latrines of so old-fashioned a pattern that night-soil

collection was required, and his trumpet roar at some stage of each inspection could be relied upon. Some of the language, too, was directed

at portions of the training programme, especially those which included saluting – in democratic New Zealand, every man was as good as his master and

saluting to the recruits implied subservience – and “one-stop-two”, the marching and drilling periods in which each man had to cry aloud the phrase

in time to the beat of his feet at the halt or on the turn.

Reveille was at 0600 hours, sick and defaulter parades at 0615,

breakfast at 0700 and first parade at 0830. Morning training finished at 1200 and lunch was at 1215. The afternoon’s training began at 1330 and ended at

1630. In the hour following, the troops bathed and showered and prepared for dinner at 1730. The bugle sounded lights out at 2215 hours. On Saturday mornings,

training was replaced by a period called interior economy when the sleeping tents were emptied and tidied, floors were scrubbed and paillasses aired.

Both reveille and breakfast were an hour later on Sundays. Leave was granted on a generous scale on Friday nights and from Saturday midday until Sunday

midnight.

Parts of the ordinary day soon came to possess special characteristics. Despite the loud cries of “Feet on the floor”

from enthusiastic NCOs as reveille sounded, a determined soldier might sneak another half hour of bed at the cost of some discomfort in the ablution

stands in a frantic 15 minutes before breakfast. After lunch there was a united move towards the beds and with backs down the troops indulged the ceremony

of “punishing the spine”, or “spine-bashing”, or as it was always called in the Division, “Maori P.T.” It was a golden period when no one

shouted “Do this”, “Do that”, “Swing the arms, SWING the arms”, and it had more virtues than the merely recuperative.

A good many men were finding difficulties in their adjustment to army life and in the reflective half-hour after lunch they resolved many problems.

The evening, too, had a charm for some, for a wet canteen at which handles of beer were sold was open for about two hours.

Despite the discomforts – the building was too small and the queues invariably too enthusiastic – the place became a club and a haven to the private

soldier. In it he could talk, discuss personalities, argue and even fight when an opponent would not admit the truth of an argument.

By 18 January, when the commanding officer made his first fearsome impression on the troops, the unit was not yet up to strength.

New recruits were arriving each day and many of them were posted to another rifle coy, E, which was meant to serve as a reinforcement coy

to the battalion.

The parade was the beginning of a disciplinary campaign and the checking of faults of dress, of failure to

salute and of a hundred and one things became rigorous. The publication of offences and punishment of offenders became a daily feature of Routine

Orders, and the general impression within the unit was that the CO was a “tough old bastard.” It is possible that the colonel himself wondered where

discipline ought to begin. The recruits had a bantering disregard for many of the military forms of discipline; the difficulty was to retain the humour,

but in proper adjustment to the discipline. Towards the end of January 1940, an unexpected recruit posted himself to the battalion.

Someone instantly called him “Borax”. He was a semi-fox terrier who was only a little cross-eyed and only a little lovable. He would not yield to caress

and he made his home where he pleased, without distinction as to company or platoon. He had enormous, eccentric skill as a cricket fielder, catching a ball

in the air with gigantic, convulsive leaps and snapping up a rolling one off the ground with the skill of genius. Borax trained hard for the cricket

held in the sports periods on Wednesday afternoons. At any hour of the day or night he would catch stones flung for him by the soldiers and he would

even swallow the small ones if others were thrown too quickly in gestures disparaging to his skill. No one had thought of a Borax for the Battalion.

Within a few days, no one doubted that he must stay. His piercingly stigmatic glance into nothingness, his crankiness of temperament, his marvellous

skill with a ball or stone, these and many other things about him were engaging. In any case, Borax had a mind of his own. He had apparently decided

to stay and that, for the time being, was the end of the matter. By the beginning of February, the unit morale had been tested by

heavy falls of rain creating slush about the test lines, by the saluting and other formalities attending the first pay parade, and by an extraordinarily

dismal sounding by an officers’ chorus of “The Road to the Isles” at a camp concert. Serge dress of Great War pattern, with a choker collar and many brass

buttons, had been issued for purposes of leave to all except Pte Dyer, of A Coy, who was as tubby as his nickname and who had to wait two weeks for the

camp tailor to make a suit of large enough size.

The training was now becoming more extensive. On wet days, lectures were held inside.

Map reading, marching by compass at night, and training in anti-gas warfare, were some of the subjects taught. There was a heavy accent upon anti-gas training.

Many soldiers suffered the curious effects of a not unpleasing disease, believed to be induced by the out-of-doors, and passed into a slumberous

state between waking and sleeping as the first words of a lecture were spoken.

As January ended and February began, it was obvious that many rough edges were being whittled. Days were now being spent upon the

rifle range and a few Bren guns were available for instruction. On 7 Feb, the first route march was made from the camp to Wallaceville Bridge, a

distance of about three miles, and lunch was taken in the field. On 9 Feb, the first of many injections was given, this being for TAB. The normal

reaction was a symptom of influenza, but despite the general knowledge of the proper way to treat influenza, a bewildering variety of treatments was tried.

It was considered by one school that the patient should lie down and rest, and by another that activities should be normal. D Coy played cricket and bodies

were carried from the field. Another coy went for a march and a truck had to be sent to bring in the sick. B Coy rested and Pte J Green had an attack of what

was roughly diagnosed as delirium tremens. It was all highly confusing. The one solid discovery was that it was unwise to take a drink after a TAB injection.

The battalion on its first march marched to its pipes and drums. Col Andrew’s affection for a pipe band had become known and

members of the New Zealand Scottish Society, through Mr I.D. Cameron of Featherston, presented the unit with six pipes and six drums. Several

experienced pipers and drummers had enlisted in the unit and the band was formed by L/Cpl E.C. Cameron as the NCO in charge. In the few weeks

before the route march, the band had practised enough to develop some of the skill for which it later became known in the Division, in which it

was the only unit band. Much will be said at intervals of the unit band. It became a source of pride to the battalion and the rugged individualism with

which, in the early stages, the bandsmen wore down criticism became the general property of the battalion. Inventiveness a

characteristic of the Division, was developed in the unit by further falls of rain and unusual but effective methods were employed to deal with

leaking tents, wet clothing, and wet blankets. Night marches were held and on some of them the transport and carrier platoons practised with their

vehicles. The carrier platoon also spent time training with the Bren guns with which the vehicles were equipped. The commander

of the Fifth Brigade, Brigadier J. Hargest, DSO, MC, inspected the unit towards the end of February. He was an experienced soldier and the satisfaction

he expressed with the standard of training and the tone of the battalion was not light praise.

March promised well from the beginning. The recreational training was now becoming extensive and fitness among the troops was

increasing rapidly. Inter-coy rivalry was also being steadily developed. Even E (coy), the last and loneliest, had a spirit second to none in the

unit. Early in March, a mile run for all of the coys was held on the Trentham Racecourse, next door to the camp and even those men of little athletic

ability made grim efforts not to whip in the field. To be last in a race or to do something inefficient on a parade was an act of neglect, particularly

if the act affected the standing of the coy, and even the hardy made [excuses] to avoid the free criticism of such folly. The battalion, however, was

not developing into a collection of Little Lord Fauntleroys. A note in Routine Orders at the end of February sternly forbade piquets in the wet

canteen to drink on duty.

The Governor General of New Zealand, General Viscount Galway, inspected the battalion on 6 Mar and

warmly praised what he had seen in a letter he despatched to the commanding officer. This was praise indeed, but in spite of it, the reaction was

smug. This was, on the part of the troops, an evil fault, but their excuse had a point. After the parade itself, the arms drill and the marching

and the niceties of a formal parade, the “Old Man” himself, Col Andrew, had been distinctly heard by the battalion to speak words of praise. So

unusual an event was cause for the belief that if the parade had been good enough for the colonel, it must certainly have been good enough for

the Governor-General.

By now the battalion was possessed with excitement. Final leave was promised. Rumours sprang from nowhere.

The unit was to sail on such and such a date, Hitler’s “phoney” war on the Western Front was to end and there would soon be action.

All of the stories were straight from Army HQ. But there was no general agreement on dates or places or, in fact, in anything as the

rumours swept from end to end of the camp and carried over to muttered speculation in the tents as one by one the men dropped into sleep.

On 13 Mar, all ranks were placed on Active Service. On that day, the few South Islanders left for their homes.

The rest of the unit marched out to leave on the following day and the camp became a forlorn and lonely place. It was a minor curiosity

of the war that Trentham Camp, clothed so richly from Great War days in military associations, seemed always to become a little careworn after a draft had gone away.

|